Filmmaker Barry Avrich answers audience questions following the STF screening of his film about Hollywood mogul Lew Wasserman. © Jasmin Chang

This post was written by STF blogger Krystal Grow.

There was a time when movies were made by men with relentless energy and a uncompromising quest for greatness who made some of the biggest films in Hollywood history possible, and changed the landscape of how major motion pictures were made forever.

Lew Wasserman grew up on the “rat infested” east side of Cleveland and got his start in show business in speakeasies and brothels in the 1920s, where he became good friends with rising stars and influential mobsters. In 1936, he became a publicist for MCA, then a musical booking agency with intricate ties to the Chicago mob. By 1938, MCA was managing 90 percent of the Chicago’s nightlife talent.

Over the next four decades, Wasserman transformed MCA from a one-trick booking agency to a multi-platform conglomerate, producing radio shows and motion pictures, and later spearheading the company’s foray into television, a move many other entertainment agencies and media companies were reluctant to make. But Wasserman, now a power player in Hollywood with a roster of influential friends, executed a strategy that allowed him and his company to dominate a fledgling medium, producing shows like Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Amos and Andy, Dragnet, Wagon Train and The Jack Benny Program.

He also pioneered the TV mini-series, an innovation that further solidified his role as a force to be reckoned with in the increasingly competitive world of movies and television. In a deal that was unheard of for it’s time, he brokered the purchase of Paramount Pictures’ entire pre-1950s archive, which he ran in syndication, another first for the last great Hollywood mogul.

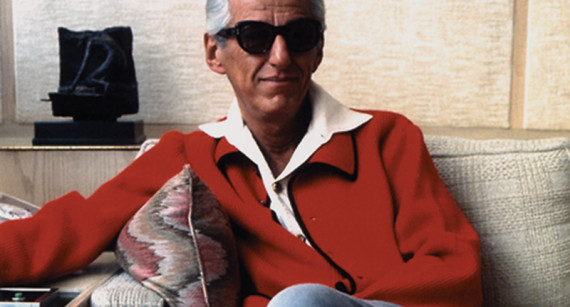

As famous for his commanding demeanor as he was for his resistance to accolades and public appearances, Wasserman captivated director Barry Avrich to follow his career for much of his life. Avrich committed to the idea of making a film about his legendary status among Hollywood high rollers.

“I was one of those nerdy kids reading Variety from age eight, so I followed him and I watched him and I was amazed at him and the entirety of his career. I knew that this was going to be a complex film to make about six decades of power,” Avrich said in a Q&A following the screening of the film at the Stranger than Fiction series at the IFC Center. A revealing look into the man behind mega hits like JAWS, THE STING and AMERICAN GRAFFITI, THE LAST MOGUL is a film as much about an individual career as it is about an entire industry, one that’s seen drastic change at the hands of technology, consumer culture and the constantly evolving Hollywood studio system. It’s a chronicle of one man’s unprecedented rise to power, and a shocking and complicated series of missteps and bad deals that led to his demise. But the legend he left in his wake shaped the way Hollywood as a whole functioned, and left generations of would-be moguls still struggling to achieve even a fraction of his greatness.

FULL Q&A

Thom Powers: What got you started on making a film about Lew Wasserman?

Barry Avrich: I met Lew and I told him I wanted to make a film about him and he said, ‘It’ll never happen whether I’m alive or dead.’

Powers: What did you know about Wasserman that made you want to know more about his career?

Avrich: I was one of those nerdy kids reading Variety from age 8, so I followed him and I watched him and I was amazed at him and the entirety of his career. I knew that this was going to be a complex film to make six decades of power. And the Wasserman family came after me big time. I’d have interviews scheduled with major power players and [the family] would make phone calls and say, “No, you’re not going to participate in that film” and then I’d have doors slammed in my face, and in studios setting up. I was followed. I was threatened.

Powers: But for all that you have some incredible power players, Jack Valenti, President Jimmy Carter, big producers…

Avrich: We got that in the can before the Wassermans could really come after me. Pleshette, and Jack was great.

Powers: After they gave the interviews did they have second thoughts about them?

Avrich: Jack did. He started making demands about seeing how he’d answered questions and how he fit in, but at that point he had signed a release so there was nothing he could do. Pleshette was the greatest. I still, to this day, do not understand why she showed up. I think she wanted to kick the tires for Edie. She gave me the all time great line. In between setups I asked, ‘What do you attribute your career and the longevity of your career to?” and she looked at me and she said, “I don’t have a gag reflex.” About a year later, I walked into a restaurant in LA and she loved hanging out with gangsters and she was married to a pretty shady guy. I walked in and she caught me in the corner of my eye and she said, ‘Hey! Where’s my f**king DVD!’ and I brought one over right away.

Powers: After the film was completed did you get any sense of what the Wasserman family thought of it?

Avrich: I tried to make peace with them along with way. I took out ads in The Hollywood Reporter saying literally ‘Dear Casey, I’m going to be respectful of your grandfather’ and there was no response, other than a couple of great letters, frameable letters. We never spoke, years later, before Lew Wasserman passed away a friend of mine ran into Edie at the Peninsula Hotel. They got friendly and she said my friend’s from Toronto and [Edie] said ‘you know, a lovely man from Toronto made a film about my husband.’ The odd thing was at the opening, all of Hollywood was invited to that film and the publicist made a mistake and sent an invitation to Edie and all of a sudden there was a tsunami of cancellations, so she had the last laugh.

Audience: Why not David Geffen?

Avrich: I have to remember whether or not we approached him. David, as you know, other than that documentary (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2515126/ ) a year and a half ago he gave no interviews either, and that documentary was beyond flattering.

Audience: During the Matsushita sale, to what extent do you think Lew created the WATERWORLD debacle as a way to make that sale?

Avrich: I heard that, I mean, it’s hard to believe. It was hard to go into that in the film because it took us down another road. It’s mythology, but who knows? It wouldn’t be beyond Lew to do that.

Audience: Because he hated Ovitz, who said he was the most powerful man in Hollywood, do you think he turned the buttons on Ron Meyer?

Avrich: Absolutely. I can’t tell the story here, but when the film opened and got a great review in the New York Times, I got a call from Ron Meyer saying “Will you come and screen the film for me, just the two of us, and then we’ll have dinner and talk about the film?” And Ron Meyer had the most unbelievable, scandalous stories about Ovitz. It was a great dinner.

And I have to say filming Ovitz was next to impossible. He cancelled every day, yet his ego was such that he had to be part of the film. I had to meet with his art curator to talk about what paintings would be behind Ovitz while we were filming. I signed this ridiculous release about his participation. It was insane. But he had to be in it.

Audience: It was said that Lew Wasserman dictated the headlines to Variety around the Ovitz deal, and said “Ovitz can’t close his own deal.” Is that true?

Avrich: It is, yeah.

Powers: So you’ve made films about Wasserman, Harvey Weinstein, how do you compare these different power brokers?

Avrich: I’ve done about 32 docs. I think my box set of moguls is now done. They’re all Shakespearean. That’s a bit cliché, but there is that point where you’ve achieved great wealth and money is no longer important, and that reach for power becomes an almost Icarus type thing. All these people could have been more than happy with the wealth that they had, could have been great footnotes in history had they stopped. But there always has to be something pushing them further. And they’re all the same. Harvey was the same as well.

Powers: Are there are stories you got that you couldn’t put into the film that are memorable?

Avrich: Well, there’s that classic thing where the minute the camera stops, everyone has a great story. Lew’s connection to the mob, though we flirted with it in the film, was way deeper, and I think that’s what the family was most worried about. But Lew made sure he was almost antiseptically pure.

Powers: Is there a contemporary mogul you’d be drawn to enough to make another film?

Avrich: I don’t think so. I mean, I think Lew in a lot of ways was the last mogul. When I was making that film, at the time, now 10 years ago, people would say ‘Harvey Weinstein,’ but the business has changed. You don’t have those kinds of people anymore. It’s very difficult to even mention moguls’ names today.

Audience: Who were the people you coveted the most that slammed their doors, and was Spielberg one of them?

Avrich: Yeah, he was. And he was scheduled to be filmed as well, but Casey got to him that day. Tom Pollock, Ivan Reitman had told me great stories about how Lew had given them their big break. Clinton was ready to go but famously has his heart procedure, so I settled for Jimmy Carter. I asked Carter if he feared Wasserman and he said that if he got a call from Gorbechav and Wasserman, he’d take the call from Wasserman.

Krystal Grow is an arts writer and photo editor based in New York. She has written for TIME LightBox, the New York Times Lens Blog and the DOC NYC blog. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram @kgreyscale.

Related Film