“Comic anarchy on a splendid level. I loved it!” – Mel Brooks

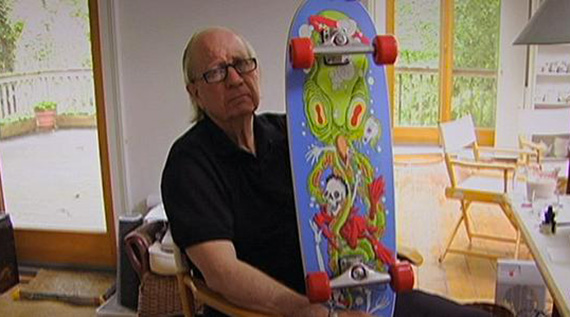

Cartoonist Gahan Wilson is revered for his macabre and hilarious work in The New Yorker, Playboy and other publications. His bulbous creatures are so distinct, you can pick out his style without a signature. With all his ghoulish humor, what makes this guy tick? Steven-Charles Jaffe, a Hollywood producer whose credits range from GHOST to the Nicholas Meyer thriller TIME AFTER TIME, directs this engaging profile exploring Wilson’s world. Jaffe interviews Wilson’s diverse fan club including Stephen Colbert, Lewis Black, Randy Newman, Hugh Hefner and others. He also examines the world of The New Yorker, interviewing David Remnick and Roz Chast and looking at how cartoons for magazine are pitched, bought, or rejected.

Excerpt from an interview with Gahan Wilson by Stanley Wiater from gahanwilson.com

WIATER: Going back quite literally to the very beginning, could you relate the tale of having been “born dead?”

WILSON: That’s the truth. I came out blue and unbreathing. The doctors were going to forget it, to console my parents and tell them, “Better luck next time.” And the family doctor did happen by and looked in and saw the event. He came in and ducked me into hot and cold water…that literally saved my life! What interests me is that it probably did have an effect–I think the whole birth process is pretty fierce, anyway. The French have a marvelous method where they’re born in darkened rooms, then immediately slid into tepid water, and it’s very peaceful–which makes complete sense to me! The result is that they all have this marvelous sort of Buddha expression on their faces, but I don’t think any of them will become macabre cartoonists!

WIATER: A “chicken or the egg” question: Which came first, the macabre drawings or the macabre sense of humor?

WILSON: I don’t know. I was apparently always very much into drawing, and also drawing odd things. We came across a fascinating trove several years ago. My mother was always saving stuff– which I didn’t not know about– and they are cartoons I did when I was a teeny little kid! Monsters, skeletons, all sorts of stuff like that. So I was into that sort of thing way back then.

I don’t know when the humor got started, quite honestly. But it’s always been there. By and large, I think, people are set at a terrifyingly early age, , so far as their conceptual equipment is concerned. I remember, just the other day, Nancy and I saw this worried baby, and he was a businessman, with that sort of preoccupied little frown. But that’s it. You’re programmed very, very early on, genetically.

WIATER: Has any contemporary writer come to you and admitted that something he wrote was inspired by one of your cartoons?

WILSON: It’s happened a couple of times. Steve King told me that one whole section of ‘Salem’s Lot is based on one of my cartoons, and he brings me up in some other parts of the book, too. But if you just hang around long enough, you sort of become part of these people’s psyches. And they grew up with you. So just as various people bent me in different directions–and I’m very grateful for them having done so–I’ve apparently “bent” a few in turn {laughs}

WIATER: Not to brashly ask, “Where do you get your ideas?” but could you cite an example of where a cartoon was inspired by something you witnessed in real life?

WILSON: At Bloomingdales, on the escalator, there was a couple of nuns in their habits. And one of the nun’s habits actually got caught in the thing. In real life, what happens is that there’s a little doohickey that halts the apparatus. But I quickly whipped out my little notebook and jotted the incident down. It later appeared in Playboy–the one where the people are being ground into the escalator. It was something that was simply too good not to use. But usually what happens is that ideas perk through, and eventually what emerges has gone through some change.