Description from TIFF 2009 catalog by Thom Powers:

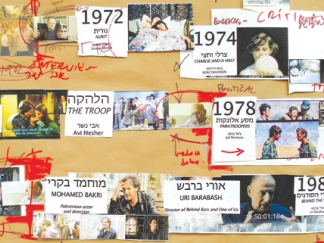

During the period covered in part 1 of this history, Israeli filmmakers tended to focus on the dream of their country. Part 2 picks up in 1979, when they were starting to explore the gap between the dream and reality. Films like 1982’s Chamsin began taking a sympathetic look at Palestinians, breaking with the conventions of Israeli cinema that treated Arabs the way American westerns treated Indians, as the default bad guys.

“We were much closer to peace in 1984 than we are now,” says the actor and filmmaker Mohamed Bakri, who played a Palestinian freedom fighter in the 1984 prison drama Beyond These Walls. The Israeli cinema of the eighties was full of Romeo and Juliet stories between Jews and Arabs. A dialogue between the two cultures was taking place in the movies a decade before it began among political leaders. In the 1986 film Avanti Popolo, set during the Six-Day War, director Rafi Bukai flips around Shylock’s monologue from The Merchant of Venice. In this case, it’s an Arab who says, “If you prick us, do we not bleed?”

The film critic Nachman Ingbar stands out as an eloquent voice interpreting this period. “At a certain stage,” he says, “you’ll have to ask yourself if your truth is better than the truth of whoever you’re fighting against.” The 1992 film Life According to Agfa typifies the relentless questioning of Israeli society. Its harsh depiction of the Israeli Defense Forces was extra shocking, given that director Assi Dayan is the son of the country’s military hero Moshe Dayan.

Over the past fifteen years, Israeli cinema widened to explore issues of sex, religion and new immigration. Director Amos Gita&”239; discusses taking on religious conservatives in Kadosh, released in 2000. The actress and filmmaker Ronit Elkabetz describes the emergence of female voices with a clip from her 2004 film, co-directed with her brother Schlomi Elkabetz, To Take a Wife. And Dover Kosashvili, the director of the 2001 international breakthrough Late Marriage, speaks of not wanting to choose between hope and despair. As he puts it, “Reality always contains everything.”

About the director:

Rapha&”235;l Nadjari was born in Marseille, France, and now lives in Israel. He began his career in French television before turning to cinema. He has written and directed the features The Shade (99), I Am Josh Polonski’s Brother (01), Apartment “5c (02), Avanim (04), which won the Prix France Culture (Cin&”233;ma) for French filmmaker of the year at the Cannes Film Festival, and Tehilim (07). A History of Israeli Cinema (09) is his first feature documentary.