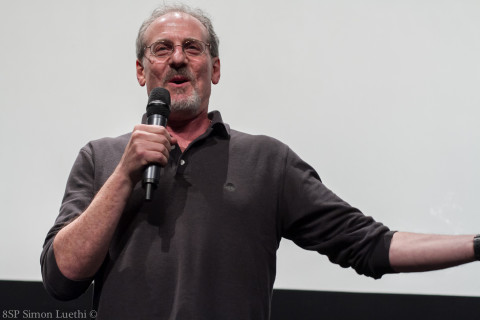

Doug Block shares tips for producing personal documentaries after STORIES WE TELL. Photo by Simon Luethi.

Sarah Polley is best known as an actress and a director of narrative feature films. She can now add documentarian to her list of credits, as she recently directed the personal film Stories We Tell. The film, which screened at STF on Tuesday, explores Polley’s family history and uncovers secrets about her parents that she had long questioned and wished to understand. Stories We Tell uses interviews with Polley’s relatives and family friends, archival footage, and experimental techniques to investigate the nature of truth and memory. By closely examining her own history and background, Polley is able to provide unique insight into the ways in which families construct and comprehend the complex narratives of their lives.

Filmmaker Doug Block, who consulted with Polley early in Stories We Tell‘s production process, was present for the post-screening Q&A. He spoke with STF’s Hugo Perez about Polley’s process, as well as his own process when making personal documentaries.

Stranger Than Fiction: Doug, can you tell us a little bit about how you got connected to this film?

Doug Block: Sure. In addition to making my own films, I produce films for other documentary filmmakers, and I do consulting. About four years ago, I got a call from somebody from the National Film Board of Canada, saying “Sarah Polley is a big fan of your film 51 Birch Street and would like you to come up to Canada and mentor her for a few days for this program we’re doing.” I said, “Okay. That sounds really good.” The National Film Board of Canada produced the film, and Sarah said the most amazing thing about it was that they kept encouraging her to be more experimental and more groundbreaking. The one imperative they gave her was to go as far outside the box of documentary as she could go. Anyways, I was a fan of hers from her fiction films and from her acting, so I embraced the opportunity.

I don’t want to pretend I had some big, undue influence over this film, but it was an interesting time, because she was still trying to figure out what the film would be. She told me the story – it took her almost a day to tell me this amazing story, and my jaw just kept going wider and wider. But she had all these really outside-the-box ideas that didn’t end up in the film. She was going to have herself, Harry, and her dad go up on stage and perform the story in front of a live audience, including the family members. So that was one thing. There was going to be a lot of animation in it, there was going to be all sorts of experimental stuff, and strangely enough, she really downplayed the reenactments. I saw this for the first time a few weeks ago, when it played at New Directors/New Films, and I’d totally forgotten about that, and it wasn’t until halfway through the movie that I went, “This can’t be. This can’t be home movie footage.” I’d be really curious to poll everybody about when you figured out that this was not home movie footage. For me, it was the memorial service, when you see Harry in the background. (laughter) And how it all had the same color temperature, no matter what situation it was in. (laughter) It all had the same kind of camera movements, it was all slightly out of focus, and the mother looks so different in different shots.

STF: The film and the storytelling is simple and direct yet profound at the same time. Can you talk a little about your own experiences? When you decide to tell your own story and share your story, what’s the mental process that happens?

Block: “Are you fucking nuts?” I think is the first thing I think. I mean, that was a question Sarah asked, because she was really wrestling with this idea. She was profoundly uncomfortable with the idea of putting her family out there so publicly. So she asked a lot of questions about what that felt like and why I made that film, 51 Birch Street, which was the first really personal film that I made about my family members. But I never intended to make that film, until I was actually making it.

I don’t want to presume that people have seen it, but 51 Birch Street was a film about all of these discoveries that I made after my mother died kind of suddenly and unexpectedly, about 12 years ago. After what we all thought was a very happy 54-year marriage, my father calls three months later from Florida to announce he’s moving in with his secretary from 40 years ago. They married and sold the family home in Long Island, and I went out there with my sisters a couple weeks before the movers came. Among other things, I discovered three large boxes of my mother’s diaries.

I never intended, even during that time, to make a film about this, except my father was the kind of guy who never talked about himself and his feelings, and I had taken my camera with me, thinking I was just going to get some last shots of the house before it all went away. I threw a couple of questions at my father, and for the first time, he started opening up about my mother and about the marriage. I was fascinated, and I thought, “Oh, Dad wants to talk. Great.” I went back a couple days later, just to keep the conversation going, and at one point I asked him, “So do you miss Mom?” And he goes, “No.” I swear to God, in that moment, I went from not making a film to making a film. (laughter) I realized, like, “Oh my God, this is not just a story about our family. It’s a very universal story about whether we know our parents and, if we had the chance to get to know them, would we really want to know them?” (laughter) Do we really want to get underneath those family secrets that may come popping out if you open a thing like your mother’s diaries? And then do you share that with the world?

STF: I guess it depends at what point in your life you find out about the secrets.

Block: Yeah, I was old enough. I’d gone through some therapy, so… (laughter)

STF: So you were ready.

Block: I guess. You’re never quite ready for that. I mean, you know, I think what was really helpful for me was that I had made two films before that, and the film I’d made right before that had gone to Sundance. So when I thought to myself “I can’t believe I’m doing this to my mother; can Jews burn in Hell for doing this to their parents?” I kept reminding myself, “You’ve made films before. You fooled them last time – it got into Sundance – and you’ll fool them again. Just keep at it.” Personal films are so hard to do because you’re so close to them. To have that objectivity and distance to pull yourself back and see yourself as a character in a story, not as therapy but as entertainment for audiences, requires a certain amount of life experience and security. I’m just in awe of Sarah, who was half my age when she made this film and tried to wrestle with the same demons. She just blows me away.

STF: I suppose it’s all about finding your voice, or having a voice you feel confident in.

Block: And also having a really great editor helps. That’s the big thing for making these kinds of films. There are quite a few really great makers of personal documentaries who edit their own work: Ross McElwee, Alan Berliner, Nina Davenport. I don’t know how they do it. I honestly don’t. For me, it’s just really, really critical to have a collaborator like that who doesn’t know my family and who’s helping me to see it with some distance. This is the second time I’ve seen Stories We Tell, and it’s really well edited. I mean, it’s just so beautifully edited.

Audience: Do you journal? Or did Sarah journal? Is journaling part of the process of finding your voice in the story you’re trying to tell?

Block: I journaled way back. After finding my mother’s diaries, I stopped. (laughter) I burned all my diaries. (laughter) I do. I journal to the extent that I keep a notebook, and I’m always throwing my thoughts down there. I can’t speak for Sarah, although I do know that she journaled over a long period of time.

In my notes to myself, I’m constantly trying to figure out what my role is in the film and what’s the film really about. And, underneath that, what’s it really, really about? Because I think with personal documentaries, it’s really important to find a bigger theme that’s going on underneath than just your family story. Stories We Tell has many interesting themes: memory, truth…

STF: The nature of love and family.

Block: Yeah! And who owns the story, and if there’s such a thing as owning a story. I think that is very helpful to me, and it’s always helpful in the process of doing it. Particularly when you’re shooting, because I think it’s important in a personal documentary to understand your role in the film, even as you’re making it.

With 51 Birch Street, I knew I had two weeks to shoot the film from the moment I decided it was going to be a film. My father was going to move, and I knew the story would end then. And during that two-week period, I was furiously writing away every night, like, “What is this film about? Okay, I’m making this film. What’s it about? What’s my role?” I was close to my mother and not so close to my father, so I decided my role was to be the aggrieved son trying to get the goods on my father. So that when I interviewed him, I would know where I was coming from in the film. But other than that, you can’t figure your role out too deeply.

So much of this is created in the editing room, which is another reason to work with a really good editor. You’re literally writing the film. Maybe not narrating, but the editing is kind of the writing. And I know that was the part that drove Sarah the craziest, because she writes her own narrative films, and she loves writing but hates editing. Or it’s the most painful and difficult part of the process for her.

Audience: I wanted to ask a related question about figuring out your character or, in this case, her lack of one. I think that was an interesting choice, that Sarah’s the only really opaque person in the film. She keeps a real directorial distance. Compared to somebody like Ross McElwee, who’s very much looking at himself, she looks at everybody else. Can you speak to that decision and what that might mean?

Block: It was a choice she made to let the family tell the story. I only know that it was really, really difficult for her to give up control and put it in the hands of everybody else in the family, because she doesn’t buy into some of the other perspectives. She had to allow everyone to tell stuff that she thought wasn’t truthful, or wasn’t accurate, or she saw in a different way. I know that was really difficult. But I thought it was a really interesting decision.

In a sense, the film is her spin on the fact that she can’t get at the truth, because it’s only coming back at her in fragments of what everybody else says. And everybody has their own vested interest in their story. They want to make themselves look good sometimes, certainly in the case of Harry and her dad. When they started to take ownership of the story, they did it in large part to make themselves look good. Everybody has motives. I thought it was a really, really interesting choice for her to be the director. I thought it was really brave of her to not talk about her feelings, or to do it just sort of tangentially.

STF: The only other character who doesn’t really speak is Diane, the mother. Both Sarah and Diane, you feel them through what everybody else is saying and through Sarah’s directorial choices.

Audience: Do you think using the staged reenactments were a bit of a distraction at times? They lent themselves to the storytelling, but as I was watching it, I was dissecting it and trying to figure out if it was real or not, and that took away from the rest of the story. In retrospect, do you think it helped or detracted from the story?

Block: I’m curious: How many people felt distracted from the story by the reenactments? (Pause) I see one and a half hands. (laughter) I don’t know. I thought they were really effective, myself. Even after I knew they were reenactments, and, actually, almost more so after I knew they were reenactments. But that’s just me. I don’t know. I just thought it was really…to me, it was helpful to get into the story.

Audience: Right, but then you find out they’re not the actual people. So you may not care as much. Like, it’s just some actor, it’s not the mother, it’s not the father…

STF: It also brings into question the whole idea of memory, you know? Like, what we think of as our memories are just as deceitful in a way as staged reenactments on Super-8.

Block: One of the films that this film called up for me is actually my favorite fiction film of all time, Citizen Kane. I’d totally embarrass Sarah by saying that this is like the Citizen Kane of documentaries. (laughter) But I think there’s quite a few apt comparisons, such as the use of overlapping stories, showing that everyone’s seeing it from their perspective, the reenactments, the trying to get at who the main character is…

STF: The other film that it reminded me of was Guy Maddin’s documentary, My Winnipeg. Has anybody seen that film? In that film, he stages scenes from his childhood with actors, but he tells you that he’s hired actors to play his mother, and you see them setting up these scenes from his childhood. Have you seen that film?

Block: Yeah, I did. It’s another visually beautiful film.

Audience: You always give great advice to other filmmakers. Who do you go to for advice?

Block: That’s a really good question. You know, when I’m starting a film, I work with a great producing partner, Lori Cheatle. We’ll hash out ideas together. And when I’m working on the film, it’s the editor. It’s really close collaboration and my favorite part of the process.

It’s a kind of lonely endeavor, because, in a way, advice should be taken with a grain of salt. Sometimes the opposite of good advice is true as well. Like, when you make a documentary, you should do your homework and find out how to prepare a budget and where to get the funding from and set up a website and a blog and get on Facebook and Twitter – you know, all these things that you should do. But on the other hand, sometimes you’ve just got to take that leap off without knowing what you’re getting into, because if you really do know what you’re getting into, you won’t do it. (laughter) So both are solid advice. Oftentimes, you just kind of go with your gut. One of the great things about documentary filmmaking is you can just start doing it. Once you get the impulse to make a film, you just start doing it. And then you get into heaps of trouble. (laughter)