Stranger Than Fiction co-presented the film Cinema Komunisto at the 2011 Tribeca Film Festival.

Viewers of Mila Turajlic’s film Cinema Komunisto might be surprised to learn that Yugoslavia’s state-run Avala Film Studios was not dedicated solely to enlarging the cult of personality surrounding Joseph Broz Tito, although it certainly did not shrink from that task. Relying on copious amounts of research and a trove of archival material, Truajlic’s film shows us Comrade Tito the cinephile—one who watched a film almost every day, and transformed his Yugoslavia into a prolific locus of filmmaking, for both artistic and propagandistic purposes. The heart of the film lies in the scenes bearing Tito’s personal projectionist, Leka Konstantinovic. In a powerful moment, Konstantinovic is shown arriving at Tito’s old estate in Belgrade for the first time in decades, where he ceremoniously hands over his key to the property to its current caretaker, who receives the gift with relative indifference. From the front, the house, though lacking a door, appears to be relatively intact. It’s only when Konstantinovic goes inside that he, and the viewer, discover that the projected reality of the edifice’s facade masks a hollowed out shell of little substance. Following the screening, Turajlic held a Q&A with the audience. Click “Read more” below.

Viewers of Mila Turajlic’s film Cinema Komunisto might be surprised to learn that Yugoslavia’s state-run Avala Film Studios was not dedicated solely to enlarging the cult of personality surrounding Joseph Broz Tito, although it certainly did not shrink from that task. Relying on copious amounts of research and a trove of archival material, Truajlic’s film shows us Comrade Tito the cinephile—one who watched a film almost every day, and transformed his Yugoslavia into a prolific locus of filmmaking, for both artistic and propagandistic purposes. The heart of the film lies in the scenes bearing Tito’s personal projectionist, Leka Konstantinovic. In a powerful moment, Konstantinovic is shown arriving at Tito’s old estate in Belgrade for the first time in decades, where he ceremoniously hands over his key to the property to its current caretaker, who receives the gift with relative indifference. From the front, the house, though lacking a door, appears to be relatively intact. It’s only when Konstantinovic goes inside that he, and the viewer, discover that the projected reality of the edifice’s facade masks a hollowed out shell of little substance. Following the screening, Turajlic held a Q&A with the audience. Click “Read more” below.

[Photo courtesy of Cinema Komunisto]

Tribeca Film Festival Report: Bombay Beach

Stranger Than Fiction co-presented the film Bombay Beach at the 2011 Tribeca Film Festival.

The U.S. government doesn’t even consider Bombay Beach a city, instead describing it as a census-designated place (with the population in 2000 recorded at a scant 366 people) comprised of one square mile of land in the California desert that hugs the eastern shore of the Salton Sea, a rift lake whose salinity now exceeds that of the ocean. Once touted as a vacation destination for Southern California’s well-heeled, the area today scans like the physical manifestation of the death of the American Dream. Alma Har’el’s film Bombay Beach is an intimate portrait of those living in this impoverished afterworld, who strive mightily for survival at society’s margins. In some of its most powerful scenes, the film shows the children of a post-apocalyptic landscape wandering the salt-encrusted detritus of a middle-class existence that no longer exists, appropriating from abandoned houses whatever they can to aid their amusement. The film is a needed reminder that poverty in America takes on a number of forms, and is too often ignored as a topic of discussion in mainstream media outlets. Perhaps it’s the sort of story that be best relayed with clear eyes by someone like the Israel-born Har’el, someone with some objective distance on the myths of America. Following the screening, Har’el and the film’s music composer Zach Condon (who performs under the band name Beirut) held a Q&A with the audience. Click “Read more” below.

The U.S. government doesn’t even consider Bombay Beach a city, instead describing it as a census-designated place (with the population in 2000 recorded at a scant 366 people) comprised of one square mile of land in the California desert that hugs the eastern shore of the Salton Sea, a rift lake whose salinity now exceeds that of the ocean. Once touted as a vacation destination for Southern California’s well-heeled, the area today scans like the physical manifestation of the death of the American Dream. Alma Har’el’s film Bombay Beach is an intimate portrait of those living in this impoverished afterworld, who strive mightily for survival at society’s margins. In some of its most powerful scenes, the film shows the children of a post-apocalyptic landscape wandering the salt-encrusted detritus of a middle-class existence that no longer exists, appropriating from abandoned houses whatever they can to aid their amusement. The film is a needed reminder that poverty in America takes on a number of forms, and is too often ignored as a topic of discussion in mainstream media outlets. Perhaps it’s the sort of story that be best relayed with clear eyes by someone like the Israel-born Har’el, someone with some objective distance on the myths of America. Following the screening, Har’el and the film’s music composer Zach Condon (who performs under the band name Beirut) held a Q&A with the audience. Click “Read more” below.

[Photo: From left, director Alma Har’el, film subject Benny and musician Zach Condon, courtesy of Simon Luethi]

These Amazing Shadows: The Films That Make America

Written by STF blogger Deena Ecker

These Amazing Shadows is a movie for, about and by people who love movies. The National Film Registry was created by Congress in 1989 for the purpose of protecting and preserving important American films, those considered culturally, historically or aesthetically significant. Directors Paul Marino and Kurt Norton take us through a journey with these films that weave the American story. The films preseved by the Registry are not just the big movies that appear on most lists. While Gone With the Wind, Citizen Kane and The Godfather are on the list, these movies and others like them do not show us a complete picture of America. These Amazing Shadows takes us through the list in a way that demonstrates what culturally, historically and aesthetically significant means to the members of the National Film Preservation Board. Is The Rocky Horror Picture Show worthy of an Oscar? No. Is it a significant part of American culture? Yes. Will ducking and covering protect you from an atomic bomb? No. Are the films telling us it will an important piece of history? Yes. Censored films, films by women in the 1910’s, propaganda, commercials, newsreels: all these aspects of film are represented on the list and addressed in this captivating documentary. Following the screening, STF Artistic Director Thom Powers spoke with Director/Producers Kurt Norton and Paul Marino and National Film Preservation Board member Dan Streible. Click “Read more” below.

These Amazing Shadows is a movie for, about and by people who love movies. The National Film Registry was created by Congress in 1989 for the purpose of protecting and preserving important American films, those considered culturally, historically or aesthetically significant. Directors Paul Marino and Kurt Norton take us through a journey with these films that weave the American story. The films preseved by the Registry are not just the big movies that appear on most lists. While Gone With the Wind, Citizen Kane and The Godfather are on the list, these movies and others like them do not show us a complete picture of America. These Amazing Shadows takes us through the list in a way that demonstrates what culturally, historically and aesthetically significant means to the members of the National Film Preservation Board. Is The Rocky Horror Picture Show worthy of an Oscar? No. Is it a significant part of American culture? Yes. Will ducking and covering protect you from an atomic bomb? No. Are the films telling us it will an important piece of history? Yes. Censored films, films by women in the 1910’s, propaganda, commercials, newsreels: all these aspects of film are represented on the list and addressed in this captivating documentary. Following the screening, STF Artistic Director Thom Powers spoke with Director/Producers Kurt Norton and Paul Marino and National Film Preservation Board member Dan Streible. Click “Read more” below.

[Photo: from left, Kurt Norton and Paul Marino, courtesy of Simon Luethi]

Chicago Maternity Center Story visits NY

Written by STF blogger Cameron Carnegie

Like a photograph that accidentally captures something historical, the members of the Kartemquin Films collaborative who made The Chicago Maternity Center Story initially sought to bring to light the plight of women who would be affected by the 1974 closing of the maternity center. An affiliate of Northwestern University, the center offered a low cost, midwife-attended home-birth. But a deeper reality was that the center gave the women and their children a chance to live.

Like a photograph that accidentally captures something historical, the members of the Kartemquin Films collaborative who made The Chicago Maternity Center Story initially sought to bring to light the plight of women who would be affected by the 1974 closing of the maternity center. An affiliate of Northwestern University, the center offered a low cost, midwife-attended home-birth. But a deeper reality was that the center gave the women and their children a chance to live.

In the 1970s, minority women seemed to understand that having a baby in a Chicago hospital meant they were four times more likely to “die” in childbirth, and that their babies were two times as likely to die as their white counterparts. The film’s gentle voice-over delivers that bone-chilling reality with a calm detachment. The camera, unknown as a potential adversary at the time, communicates without mistake the hospital board members’ disregard for the fragile existence of the women.

None of the board members had the slightest concern for the women, who, without a $50 midwife option, had only a $600 local or $1200 private hospital delivery available to them. Advocating for themselves in front of the board, the women never mention the statistics. But as the film evolves it catches the moment—the exact heartbeat—when health became business first, and patient-care second.

The Chicago Maternity Center supporters starkly contrast the board members who are primarily men, old and white. In a lingering video snapshot, the administrators’ callousness leaps off the screen. Smirks and eye-rolling eventually come back to haunt board members lacking the media savvy to restrain their contempt. With every dismissive gesture captured, the disdain for the women is recorded. There, for posterity to view, administrators would learn their lesson—although too late for the center.

The Chicago Maternity Center Story is a black and white snapshot that today shows us that our healthcare system hasn’t come that far. That system is still driven by profit, and not our best interests.

This film illustrates the media-suppressed reality that giving birth at home is actually desirable. The environment has fewer germs and lacks many of the compromising variables and motives that exist in a hospital. The film includes footage of a young black woman giving birth at home with a midwife from the center in attendance. It shows a difficult birth (not for the faint hearted) that is actually rendered almost commonplace by the skill of the veteran midwife. The breech is merely a fact to be dealt with not a cause for panic. The young woman is lucid and calm once the birth of her healthy baby boy is over.

With the challenge of his birth overcome, the audience learns during Q&A he only lived 17 years in the neighborhood that wouldn’t qualify as upper-class. His mother, proud to have been a part of the film could only say, according to the filmmakers, “I was glad to have him as long as I did.”

Following the screening, STF moderated a Q&A with Kartemquin filmmakers Gordon Quinn and Suzanne Davenport, and film subject Laura Newman.

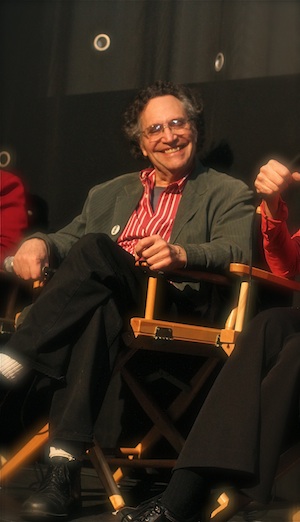

[Photo: Gordon Quinn, courtesy of Simon Luethi]

In Memory of Chris Hondros

I write with shock and sadness over yesterday’s deaths of Chris Hondros and Tim Hetherington in Libya. In February, Tim showed his short film DIARY at STF and gave a thoughtful discussion afterward. We met only a few times, so others can testify to his career better than me. But I knew Chris for many years and want to add a few thoughts.

I write with shock and sadness over yesterday’s deaths of Chris Hondros and Tim Hetherington in Libya. In February, Tim showed his short film DIARY at STF and gave a thoughtful discussion afterward. We met only a few times, so others can testify to his career better than me. But I knew Chris for many years and want to add a few thoughts.

The New York Times Lens blog has published a tribute that does a fine job of getting Chris’ attributes, the way he defied the cliches of war reporting as a person. He was level-headed, neither cynical nor indulgently romantic about his profession. He took a long view of history as the son of European immigrants who had memories of WWII. He was very good with words which you can hear in his NPR interview or read in his articles. Those pieces were often written for small publications or blogs, less for career advancement than for the urge to contribute as an eyewitness. Chris had earned the security of employment at Getty Images, but he took great pleasure in side projects like setting images to music for small performances.

He was my favorite dinner companion, possessing a rare perspective on what’s happening in the world, but also a good listener. He was quick-witted. He liked teaching. He took interest in other people’s work. One of his last Facebook messages was to congratulate colleagues who had won awards.

He didn’t have the self-destructive bent that characterizes some war reporters. He could plan ahead. We were plotting an event in Toronto this June to show his Tahrir Square photos. He was going to get married in August. Outsiders might consider his whole profession foolhardy. But I think he considered it a privilege, albeit a dangerous one. He told an interviewer, “you see humanity at its worst, but to me it’s balanced by the fact that you also see humanity at its best. I’ve seen such examples of courage and human generosity.”

The urge to make sense of his death risks its own cliches of grandiosity. If Chris had a choice of where to die, I’m sure he wouldn’t have picked Misurata – a place so remote that newspapers can’t even agree on its spelling. While it may be obscure to us, for others it’s home where hundreds of Libyans have been killed in recent weeks. Chris, Tim and their colleagues were attempting to tell that story. Perhaps we don’t like the story – it doesn’t contain the right heroes or feel destined for a happy ending. But, still, there are lives at stake of people who are as dear to their families as Chris was to me. Why wouldn’t that be a story worth telling?

If you pressed Chris about the danger of his job, he’d point out that no one gets to pick where he dies. Or when. So just hunker down, do your best work and try to leave something of lasting value. That’s what he did.