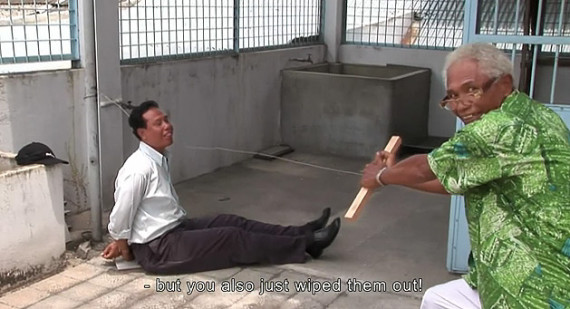

STF Artistic Director Thom Powers in conversation with filmmaker Jem Cohen (MUSEUM HOURS) following the screening of Marker's SANS SOLEIL. ©Ruth Somalo

This post was written by STF blogger Krystal Grow.

We are invited into SANS SOLEIL by the icy and congenial voice of an imaginary narrator, the only source of stability in Chris Marker‘s legendary 1983 anti-documentary which opened the 2014 Stranger Than Fiction series at the IFC Center on May 6.

An abstract travelogue punctuated by dense, poetic descriptions and lush, vibrant imagery, Marker floats through his frames with an intentional dissonance that feels both reckless and precise. Regarded as a master editor in the days before Final Cut and non-linear editing, Marker bends and twists the documentary form in a way that never claims to know the truth about anything, and questions the very nature of history, memory and reality.

The film takes massive leaps on all fronts, intellectually, technologically, aesthetically and psychologically, but at a pace that’s almost hypnotic. The female voice with the cold British accent becomes soothing to a point where Marker’s imagery starts to look like a surrealist National Geographic special, complete with viscous wildlife footage and pointed socio-cultural observations.

SANS SOLEIL is Marker’s most widely seen film, and has left an indelible impression on the cult community that’s grown around his work. Filmmaker Jem Cohen, director of MUSEUM HOURS and BENJAMIN SMOKE said he first saw the film when a group of Australian friends forced him to watch the movie soon after he arrived in the country.

“I always experience a kind of jet-lagged reverie every time I see it. ,” Cohen told STF Artistic Director Thom Powers during the Q&A session that followed the screening. “That feels appropriate,” Powers responded, as the audience slowly emerged from their Sunless-inflicted trance. “I feel like everybody needs a pause because it feels so ridiculous to do anything after seeing this film, because it’s so dense and marvelous,” Cohen said.

Even to fans like Cohen, SANS SOLEIL is essentially unknowable, a factor that Cohen said actually contributed to his love of the film. “I’m delighted to think about how utterly indescribable and unpitchable it is,” he said. “I feel like we’re in a time where documentaries are forced into situations where they have to be pitched and you’re supposed to have a one sentence line you can throw to some money person in an elevator. You cannot do that with this movie.”

Good films thrive on mystery, but Marker takes that to an almost profound level, using the conventions of documentary filmmaking to tell what could be a completely fabricated story, and by using the classic vehicle of voice-over narration to establish structure in an intentionally unstructured world. Marker takes us to places that could be familiar, but makes us question our own memories in the process of following him on his journey. We eventually come full circle, to the image that opened the film. The narrator, dictating a fictional traveler’s letters, calls it ‘the happiest image in the world.’ All the audience sees are three blonde children, staring skeptically at the camera and pondering its purpose. A fitting end to a film that defies easy answers, and demands a total dismissal of everything you thought was true about documentary filmmaking.

“It’s a film that works like memory and it works like life, so the density is to me, an appropriate function of something that is meant to feel like the way that we think, the way we remember, the way that we look and the way we experience the world,” Cohen said. “Maybe that’s dumbing down, or maybe that is just what it is.”

Full Q&A

Thom Powers: Chris Marker passed away in the late ‘90s and left behind a vast filmography that covers all kinds of topics and genres. He was also a writer that always seemed to be interested in upcoming technologies. I understand late in his life he was very interested in Second Life, the virtual reality game. Jem, Can you talk about talk about when you first encountered Marker’s work and what it meant to you?